Prometheus to Polysilicon

In previous posts, we’ve seen that the clean energy bubble of 2021 turned into an antibubble of equal proportions earlier this year. Climate change continues to progress, while the weaker companies in the energy transition are shaking out, and winners are emerging. The opportunity for investors has grown as their share prices have fallen. The sentiment against most of the sector (unloved and ignored) is what makes it so interesting.

To start investing with a solid footing in the development of the energy system, I wanted to better understand how previous transitions had occurred. What drove them? How long did they take? What challenges they face, and why did they ultimately succeed (or not)? And what can we learn about today’s change from previous transitions?

What I will publish in the coming months is the result of that research.

Absolute v Relative

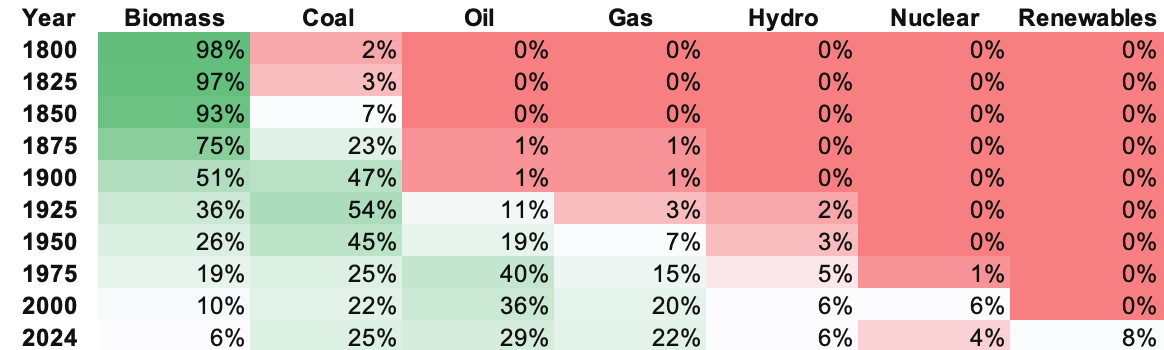

Here’s a question – do we consume more or less energy from biomass (wood, charcoal, dung etc) today, compared to 1800?

The obvious answer might be… no, of course not. Now we have powerful fossil fuels and widespread electricity. But you have to be careful with ambiguous questions. The answer is: not as a share of consumption, but in absolute terms: yes. Using available natural matter for heat and light happens at greater scale today than in 1800, despite the additions of coal, oil, gas, and electricity.

Then, 98.3% of global energy consumption was from biomass – for heat and light, and very early industry. At that time, it amounted to 5,500 terawatt hours (TWh, a unit) of energy, with another 97 TWh coming from coal. In 2024, of the energy consumed by the world, only 6% came from biomass. However, it was exactly double the amount in 1800: 11,100 TWh.

When we think about past energy transitions, one key thing to remember is “share vs absolute”. Population and economic growth means that something can grow in absolute terms, even as its share falls precipitously. While certain new energy technologies have been growing rapidly as a share of the system, the incumbent fossil fuels and their applications are often still growing in absolute terms.

The energy system is a moving target.

A Bolt of Energy

From Zeus to Thor, the lightning bolt has been the subject of myth and legend for millennia. Lightning is a giant spark between one thundercloud and another, or to the ground. Since the earliest days of civilisation, controlling the power of electricity has been seen as divine. In those times, energy came from human and animal labour, fire, and some early water- and wind- mills. Going back even further, a key energy development was evolutionary: switching from all fours to walking/running on two feet, which gave early humans an estimated 25%-50% energy saving. We’ve come a long way since then.

An ancient Greek philosopher, Thales of Miletus, is credited with the earliest recorded observation of static electricity, by rubbing amber with cloth and seeing that this could attract light objects like feathers. The famous story of Benjamin Franklin and his kite in a thunderstorm came next in 1752, before Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) experimented on frogs and found that their legs twitched when connected to a current. Was this “animal electricity”?

Not quite, as Alesandro Volta (1745-1798) later showed. The fluid in their bodies was conductive, and so when connected to the current, their legs completed a circuit, explaining the twitch. He invented the voltaic pile (pile is French for battery) in 1800, seen as the first true battery, providing a continuous electric current. He’s the reason we have the measurement “volt”.

Knitting It All Together

The Energy Transition is not one single step, from polluting fossil fuels to clean renewables, but is more like the interlocking and ever-moving staircases of Hogwarts. The simple view conjures up a straight-line view of history, which might look like this:

However, interrogate this simple narrative and you start meeting problems immediately.

Most importantly – the energy system in its entirety is made of both fuels and uses. Sources, and conversions. Supply, and demand. You can decarbonise supply, or electrify demand… Discovering petrol is one thing, building cars is another… Lighting can become cheaper and more efficient because you use electricity instead of burning gas, or because you are using LED lightbulbs instead of incandescent ones. Both sides are connected, symbiotic, feeding off and driving one another.

Both energy providers and energy uses are powerful factors in the development of the energy system – the continuous energy transition that has occurred at different speeds in different places. Piece it all together, and the history of energy looks more like a childs’ squiggle than an arrow. Today, the classic example is that shifting to electric vehicles is a good thing, but if we use power from coal plants to charge them up, the impact of the switch is lower than if the grid they’re charged from uses a high share of zero-carbon sources. In Norway, almost all new cars sold are electric, in Nairobi, almost none. Some countries have very high shares of renewables, some have barely begun.

The Historical Energy Squiggle

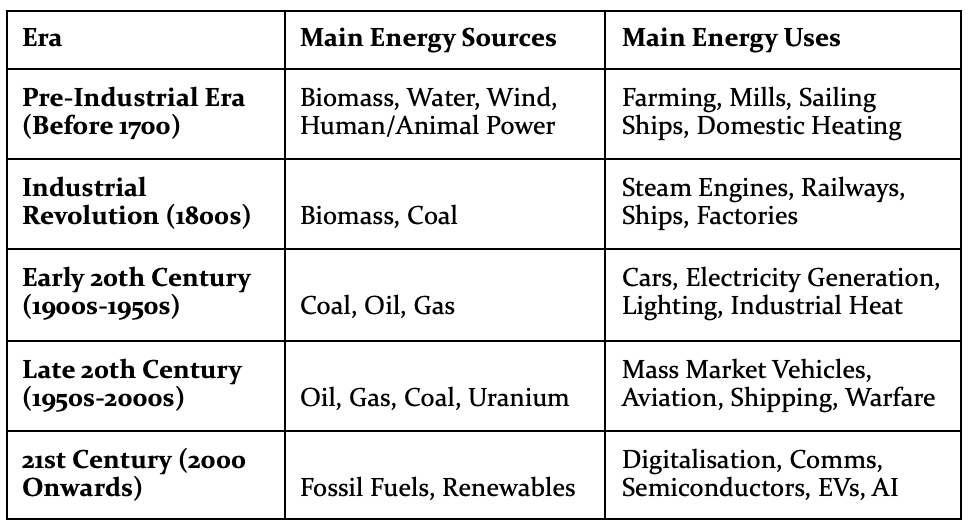

Since the Middle Ages, we have gone from muscle, animal, wood, water and horses to coal and steam, then to oil, gas, petrol engines, and electricity, all the way to today’s mix with a growing share of renewables and electric vehicles. All the while, human development has tracked our ability to convert and harness energy for heat, light, power, movement, and more.

To begin with, 100 watts (0.1kW) of sustained human labour was all the energy a person had at their disposal, which was a limitation. The 300–400W that a draft animal could provide was the first improvement, and then horizontal waterwheels could offer 5,000 W (5 kW) by the year 1000 AD. Eight hundred years later, steam engines arrived and could deliver 100kW. Modern steam turbines could deliver 1,000,000,000 W (1 GW) by 1960 and 1.8GW by 2025.

Energy Sources and Uses Over Time

Today we face a great challenge: understanding the current “energy transition” in real time. As above, we are not going through just one.

Firstly, it is necessarily different in every region, because wind, solar, and hydropower are highly dependent on the local conditions (solar in Morocco, wind in Scotland, hydro in Switzerland). As with fossil fuels, all countries have different types and amounts, and not all sources are equal.

Secondly, both the sources and uses of energy are changing. We are decarbonising electricity generation, and separately, electrifying the final consumption of energy. The two processes are connected, but distinct.

Finally, different applications are undergoing different changes. Heat, light, and movement all have different energy landscapes.

So when you think of energy transitions, don’t just think of going from wood to fossil fuels, or fossil fuels to renewables. It a much more connected, overlapping, and complex web of interactions.

As we seek to understand the nature, speed, and consequences of the current change, we can look to past transitions to help us. There is a natural instinct to forget that oil, coal, and gas were once the new energy sources, to assume that how things work is how they have always worked. Conservatism, a preference for the status quo, is typically based on what worked for people in their own formative years, rarely for anything earlier than that. No one today is defending the mule for farmwork, or the horse for commuting. It is a powerful human bias, that has shown up in every previous transition too. Every man thinks himself modern.

Long before the great eras of coal, oil, and gas, for hundreds of years we used water mills, windmills, animals, and wax candles to power our lives. Cars were a replacement for deeply-loved horses, and before all of this, all we had was our own muscle power. Progress is welcome, but was never without difficulty nor opposition. However, a study of previous transitions uncovers numerous key drivers, or insurmountable hurdles, which can help or hinder a new energy technology.

Before we embark though, it’s worth saying one thing. Energy is everything. It is the foundation of human civilisation, of life. Food, movement, muscles, lights, cars, heaters, lights, it’s all energy. It has lifted billions out of poverty into a life that until very recently, was unimaginable to even the richest rulers.

The main energy transition is not from one thing to another – it’s that there’s more and more of us, and we’re using more and more of it – and this is a very good thing. The backdrop to all transitions is rising global demand for energy. Fossil fuels have been at the centre of this success over the last two hundred years. We can celebrate their immense and ongoing contribution to human flourishing, but the strong likelihood is that their relevance will decline over the next fifty to one hundred years, or perhaps even faster than that.

The Nine

The history of energy is not a single straight line from one fuel to the next. Rather, it’s a complex web of multiple transitions in fuels, technologies, and applications. These occur at different speeds in different places, and could be broken down further, but this analysis will balance detail with coherence, by looking at a series of nine independent transitions:

Whale oil to oil

Wood to coal

Steam engines to electric motors

Gas lighting to electric lighting

Coal: rise and fall

Oil & gas

Horse to car

Nuclear’s false start

Electrification: the unstoppable force

I summarise each very briefly, before giving each my full attention in the weeks to come.

Whale oil, used for lighting, was replaced by oil partly because declining whale stocks were pushing prices higher as demand rose, and partly because oil was discovered and exploited, and was a much more energy dense fuel.

During the Middle Ages, urban growth was limited by the availability and scale of nearby forests, a problem which fell away as coal, a more energy dense fuel, was discovered. It was exploited just as forest depletion was seeing supply fall as demand rose.

Steam engines went through decades of innovation alongside the early industrial revolution. Despite their huge potential, adoption still took decades. When electric motors came along to replace steam, their adoption was also slow, as businesses were reluctant to retire valuable operating assets, instead waiting for their natural end of life to replace them, the new technology’s advantages.

Gas lighting replaced candles and oil lamps, but its fashionable heyday was brief, as electric lighting appeared offering faster, cleaner, cheaper, safer, smokeless, and precise lighting. In both instances, their huge advantages didn’t help them reach mass adoption any faster – taking more than a few decades.

The energy density of coal made it the fuel of the industrial revolution, but at a cost in air pollution and carbon emissions that saw it come under pressure from the 1950s onwards. Gas and (more recently) renewables have arrived, offering cost-competitive alternatives at scale.

As for oil, the foundation of all consumer goods and luxury experiences that fulfil so many lives around the world, it still dominates the scene today, but decreasingly so, and the loss of growth is typically a sign of change ahead.

For centuries, travel over land was by foot, horse, or carriage, and the petrol car’s arrival in the 1880s was revolutionary. Even so its expansion took decades, limited by the speed of developments in factory production methods, the road network, fuelling infrastructure, and vehicle performance.

Thanks to energy density of uranium, Nuclear seemed destined for a transition to mass adoption of its own after WW2, but safety concerns, public pressure, political wavering, complexity, rising costs, missed targets, and viable competition means it has never fully delivered on its promise.

Finally, electricity, which also began as an expensive and complex alternative, but steadily took over lighting and machinery, before generating entirely new markets in home appliances, electronics, and now transport and AI too.

Waste Not, Want Not

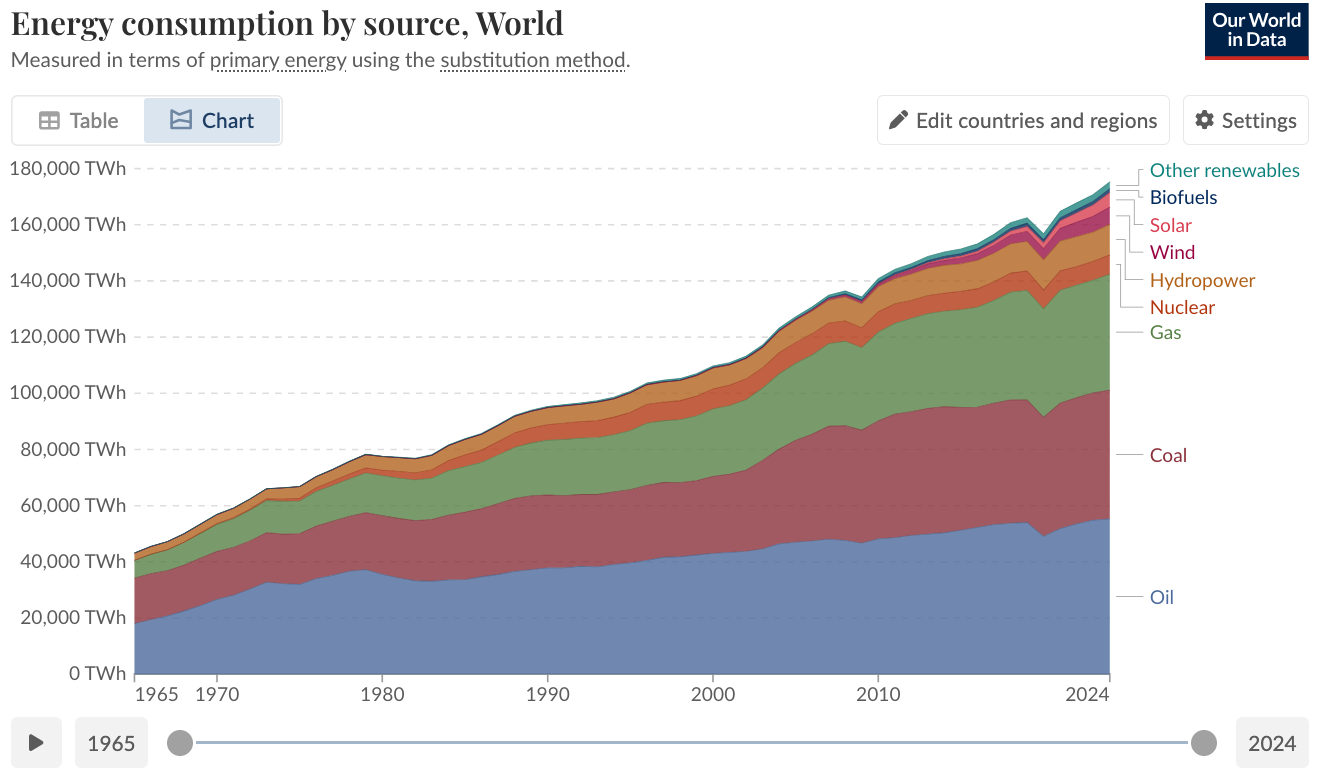

Looking only at the sources of energy, here is the data to help frame the conversation. It’s from Our World in Data and is based on a share of the total, so ignores the fact that the total system has grown.

It is also based on their share of what’s called primary energy, which ignores the fact that when fossil fuels are burned to generate movement, light, or power, around 2/3rds is lost as waste heat. Thus, in terms of useful energy delivered, the share delivered by electricity (hydro, nuclear, and renewables) rises from 18% to 30% - a material difference. To borrow an example, a VW Golf doing 40 mpg uses 1.2kWh/mile. The equivalent electric VW ID3 uses just 0.3 kWh/mile. Switching achieves a 75% reduction in primary energy demand for the same amount of travel.

Sources of Energy, Since 1800

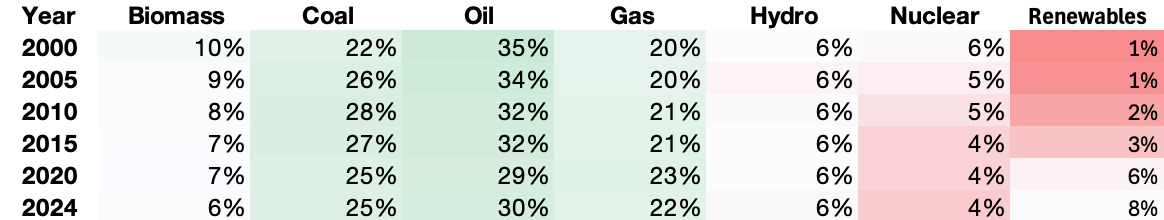

Since 2000, change has accelerated and the data has improved, so we can zoom in for a more detailed picture.

Sources of Energy, Since 2000

While these tables are still useful, they don’t even show half the story, as the efficiency of each source is not factored in, nor are developments in the end uses. The energy transition is about more than just fuels - it’s everything. Nonetheless, it’s a good starting point, and we will unpack the details further as we go.

This starts next week with something that doesn’t even register in that dataset.

A unique energy resource, with a fascinating story…

Blubber.

Very good Kit. The VW did of course lose efficiency from natural resource to electric charge. Like for like important.